North-South Commuter Railway (NSCR): Modern Train Network Connecting Luzon Island

North-South Commuter Railway (NSCR): Modern Train Network Connecting Luzon Island India launched Bharat Taxi Service as First Cooperative-Owned Digital Mobility Platform

India launched Bharat Taxi Service as First Cooperative-Owned Digital Mobility Platform India places World’s First Live Commercial Order for Hyperloop-Based Cargo Logistics

India places World’s First Live Commercial Order for Hyperloop-Based Cargo Logistics How Weigh-in-Motion Systems Are Revolutionizing Freight Safety

How Weigh-in-Motion Systems Are Revolutionizing Freight Safety Women Powering India’s Electric Mobility Revolution

Women Powering India’s Electric Mobility Revolution Rail Chamber Launched to Strengthen India’s Global Railway Leadership

Rail Chamber Launched to Strengthen India’s Global Railway Leadership Wage and Hour Enforcement Under the Massachusetts Wage Act and Connecticut Labor Standards

Wage and Hour Enforcement Under the Massachusetts Wage Act and Connecticut Labor Standards MRT‑7: Manila’s Northern Metro Lifeline on the Horizon

MRT‑7: Manila’s Northern Metro Lifeline on the Horizon Delhi unveils ambitious Urban Mobility Vision: Luxury Metro Coaches, New Tunnels and Pod Taxi

Delhi unveils ambitious Urban Mobility Vision: Luxury Metro Coaches, New Tunnels and Pod Taxi Qatar approves Saudi Rail Link Agreement, Accelerating Gulf Railway Vision 2030

Qatar approves Saudi Rail Link Agreement, Accelerating Gulf Railway Vision 2030

Why comprehensive data is key to reinventing our streets?

Decades of design and management influenced by the auto industry has shaped the American street into the place we all loathe today: congested, dangerous, loud, and polluted. After all, it was the auto manufacturers who demonized pedestrians walking in the streets and invented the crime of jaywalking in the 1920s, single-handedly transforming the street from public space for pedestrians, vendors, streetcars, and kids at play into a place where auto vehicles and their drivers seem to be the only constituents. But cities are beginning to imagine a new kind of street that brings us back to the early 20th-century roots - more liveable, walkable spaces that make it clear passenger vehicles aren’t the only users in town.

Modern policies are already prioritizing the creation of more pedestrian, bike, and scooter designated streets, as well as more patio seating and street-side dining. COVID-19 has only served as an accelerator for these changes. For instance, at the end of May, the Mayor of Los Angeles, Eric Garcetti, launched the first phase of LA Al Fresco - which streamlines approval for businesses to provide outdoor seating on sidewalks and in parking lots. Phase 2, launched last month, now includes streamlined approval for businesses to provide seating in street parking spaces, as well as lane closures, and street closures. The COVID-19 pandemic has also accelerated our already rapidly growing dependence on commercial operators. From groceries and take-out food to nearly any other day-to-day good you can think of, reliance on commercial delivery services is here to stay. Increasing commercial activity, especially as curbside use expands to businesses and other modes of transit, is a major challenge cities need to consider as they reinvent their streets for both temporary and long-term needs.

The path forward is clear

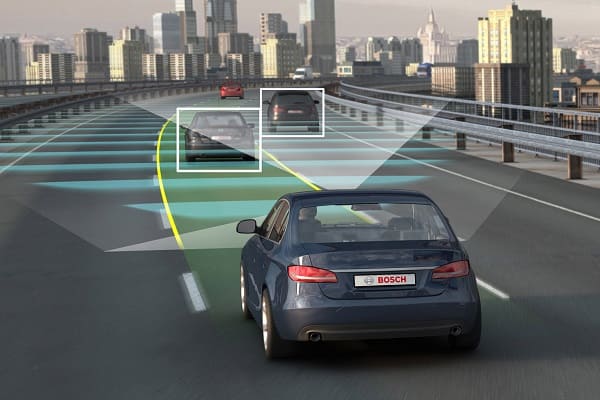

It’s clear reinvention will only work if the planning and decision-making surrounding it is rooted in comprehensive data based on the movement that’s actually happening on the ground. Without the right data, cities risk making uninformed decisions that not only fail to meet the dynamic needs of their residents, but also fail to capture the largely untapped revenue of commercial vehicle parking. In order to enact effective policy, cities must first prioritize a data-driven process that collects and analyzes information on the diverse kinds and applications of vehicles on the road (i.e. passenger, delivery, food-delivery, ride-hailing, scooters, and buses). Collecting and analyzing this data would have been utterly impractical just a few years ago, but recent advancements in AI and machine vision technology now give cities the power to fully understand their curbs. With this data at their fingertips, cities can better understand where and what adjustments are needed, allocating real-estate and aligning policies for both commercial and consumer parking. For example, identifying the volume of double-parking and average dwell times of freight and ride-hailing provides cities the data they need to get the internal support to allocate parking spaces dedicated to commercial vehicles with policies that align with their behavior. Finally, with the right adjustments, cities can unlock a huge source of revenue by effectively monetizing and enforcing short-term parking by commercial vehicles, a segment that is largely unaccounted for in today’s parking operations.

The good news is we’re already seeing cities take the necessary steps to better understand their streets and multimodal curbside demand: starting in May 2020, the city of Bellevue, WA launched a number of curbside monitoring pilots. Automatic camera-based technology is one of them, which collects data on activity across the city for each mode of mobility, including buses, passenger vehicles, and most importantly, freight and ride-hailing.

Without the right data, reimagining a street-inspired by our early 20th-century roots won’t lead to better, safer streets. Instead, we will see streets that are not only more dangerous and more congested, but that also fail to meet the rapidly evolving needs of their residents. As the use of on-demand delivery, micro-mobility, and ride-hailing continues to grow, the divide between cities that use comprehensive data to drive planning and policy-making and those that don't will become increasingly clear.