North-South Commuter Railway (NSCR): Modern Train Network Connecting Luzon Island

North-South Commuter Railway (NSCR): Modern Train Network Connecting Luzon Island India launched Bharat Taxi Service as First Cooperative-Owned Digital Mobility Platform

India launched Bharat Taxi Service as First Cooperative-Owned Digital Mobility Platform India places World’s First Live Commercial Order for Hyperloop-Based Cargo Logistics

India places World’s First Live Commercial Order for Hyperloop-Based Cargo Logistics How Weigh-in-Motion Systems Are Revolutionizing Freight Safety

How Weigh-in-Motion Systems Are Revolutionizing Freight Safety Women Powering India’s Electric Mobility Revolution

Women Powering India’s Electric Mobility Revolution Rail Chamber Launched to Strengthen India’s Global Railway Leadership

Rail Chamber Launched to Strengthen India’s Global Railway Leadership Wage and Hour Enforcement Under the Massachusetts Wage Act and Connecticut Labor Standards

Wage and Hour Enforcement Under the Massachusetts Wage Act and Connecticut Labor Standards MRT‑7: Manila’s Northern Metro Lifeline on the Horizon

MRT‑7: Manila’s Northern Metro Lifeline on the Horizon Delhi unveils ambitious Urban Mobility Vision: Luxury Metro Coaches, New Tunnels and Pod Taxi

Delhi unveils ambitious Urban Mobility Vision: Luxury Metro Coaches, New Tunnels and Pod Taxi Qatar approves Saudi Rail Link Agreement, Accelerating Gulf Railway Vision 2030

Qatar approves Saudi Rail Link Agreement, Accelerating Gulf Railway Vision 2030

How was India's first Railway Line built and opened in 1853?

India's first 33.79-km railway line between Bombay and Thane opened in 1853. However, there was an earlier plan to build a line from Calcutta to Delhi, and a rare map from 1846, which helped hail the rise of Modern India, was prepared for the East India Railway Company's initial survey.

The construction of the railway system across India during the second half of the 19th Century utterly transformed the subcontinent’s society, communications and economy. Disparate regions that were separated by journeys that could last weeks could now take a few days, if not hours.

Peoples and cultures that historically had little contact with one another could now easily interact. Products in rural India that languished far from the market could now be brought swiftly to cities and ports.

From a political perspective, it also allowed the British colonial regime to quickly move troops and civil servants around the country, solidifying its control over India.

The first railway completed in India was a 33.79 km long line of track running between Bombay and Thane, which opened in 1853.

While seemingly a modest breakthrough, everyone knew that it was the prelude to a revolution – a pan-Indian Railway network.

In 1845, the East Indian Railway Company was formed with the objective of building a line from Calcutta to Delhi. Such a railway would connect the Company Raj’s capital with the ancient Mughal capital and would serve to unite India’s most populous regions.

The Gangetic Plain was India’s breadbasket and many cities such as Kanpur and Allahabad were increasingly important industrial centres.

The railway promised that, for the first time, products and peoples could be easily transported down through the plains and even to the seaport of Calcutta. The potential was enormous, and, if the railway were realized, it would dramatically transform Northern and Northeastern India.

The East Indian Railway Company was officially floated on 1 June 1845 with £4 million in investment capital – an enormous sum for the time.

Rowland Macdonald Stephenson (1808-95), an experienced railway engineer, was chosen as the Company’s first managing director.

Stephenson and three surveyors immediately headed to Calcutta, arriving in July 1845.

George Huddleston, a later Director General of the Railway noted, Stephenson proceeded

With diligence and discretion which cannot be too lightly recommended, to survey the line from Calcutta to Delhi, through Mirzapore [Mirzapur], and so great and persevering were the exertions of himself and Staff that, in April 1846, the surveys of the whole line were completed; important statistical information obtained and an elaborate report transmitted to your Directors in London.

Copies of Stephenson’s manuscript surveys were given to the firm of J. & C. Walker, the official mapmakers of the British East India Company (EIC).

The Walker firm grafted Stephenson’s plotted proposed route of the railway onto one of its own existing general topographical maps depicting Central and Northern India and printed the present bespoke map. Copies of the map were then supplied to the Directors to accompany Stephenson’s report.

The East India Company, once an ambitious and hyperactive organization, by this time, was beset by institutional fatigue and a lack of funds. While it recognized the value of the railways to India’s future, it proved too tired to provide any leadership and ended up presenting only bureaucratic obstacles to the railway builders.

It was no surprise that following the Uprising of 1857 Queen Victoria would put the “Honourable Company” out of its misery and replace it with Crown rule over India.

In 1850, Stephenson appointed George Turnbull (1809-89), a highly experienced Scottish railway engineer, to lead the construction efforts. Turnbull would later gain great acclaim as the “First Railway Engineer of India”.

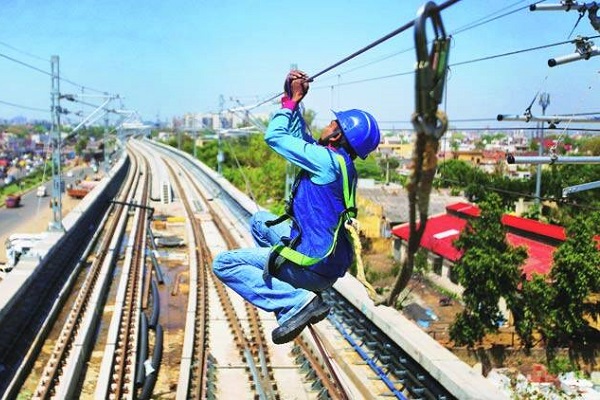

Turnbull proceeded to survey the exact line of the new route and to design the Howrah Terminus, across the Hooghly from Calcutta, which, with 23 platforms, would soon become the largest rail station in Asia. Construction commenced in 1851 and proceeded slowly due to supply problems and the continued lack of cooperation from the EIC.

The first stretch of line from Howrah to Hooghly, only 23 miles long, was opened for traffic in 1854. The construction then continued in the direction of Rajmahal.

Progress was further retarded by the Uprising of 1857, during which many supplies and pieces of track were stolen. A cholera epidemic in 1859 killed over 4,000 railway workers. Yet, the project still moved forward.

The biggest technical obstacle that lay ahead was building a bridge over the 1-mile wide breadth of the Son River, the Ganges' largest southern tributary.

This bridge (today’s Koillar or Abdul Bari Bridge) would turn out to be a great feat of engineering, being the longest bridge in India built before 1900. Commencing in 1856, it was not finished until 1862.

The line running all the way from Howrah to Benares was opened in 1862.

Another section of the line was being built separately along the Ganges Valley, with a line connecting Kanpur to Allahabad being completed in 1860, while Benares and Allahabad were connected in 1863.

By 1866, all gaps between Howrah and Delhi were filled in and direct service along the entire line commenced.

Meanwhile, the pioneering, yet tiny, Bombay-Thane line had grown into the Great Indian Peninsula Railway. By 1870, it ran from Bombay to Allahabad, connecting the two great railways and making it possible to traverse India in only a few days.

Today, the custodian of the integrated national railway system, Indian Railways, employs over 1.3 million people, runs 151,000 km of track, and operates over 7,000 stations.

The story featured may in some cases have been created by an independent third party and may not always represent the views of the institutions, listed below, who have supplied the content.

2. Hena Mukherjee (1995), The Early History of the East Indian Railway 1845–1879, (Calcutta, 1995)

3. M.A. Rao, Indian Railways, (New Delhi, 1988)